The Livingstons

A Livingston Legacy Revived

Speaker-to-Be Has Rich Bloodlines in North and South

New York Times, Monday, November 23rd, 1998 p. B1

By DAVID W. CHEN

LIVINGSTON, N.Y. – Before the Kennedys, before the Roosevelts, before the Vanderbilts, there were the Livingstons.

From the late 17th century to the early 19th century, they were one of America’s most aristocratic families, lording over the Hudson River Valley and owning more land than the state of Rhode Island has.

Firm believers in noblesse oblige, the family helped mold the republic- one Livingston  administered the oath of office to George Washington, another signed the Declaration of Independence, still another became a Supreme Court Justice.

administered the oath of office to George Washington, another signed the Declaration of Independence, still another became a Supreme Court Justice.

As the country matured, the Livingstons consolidated their status, fiercely protecting their legacy and often marrying one another to retain their land. But by the early 20th century, the Livingstons had retreated from public life, preferring instead to enjoy the view.

Now, though, after coasting for two centuries on the achievements of men in big wigs with titles like “The Signer” and “The Judge,” the family has returned to prominence, thanks to Representative Robert Linlithgow Livingston, a 10th-generation descendant of Robert Livingston, First Lord of the Manor.

Mr. Livingston, the 55-year-old Louisiana Republican who is poised to become the next Speaker of the House of Representatives, may officially be a man of the South. But his distinctly Yankee and upper-crust bloodline has prompted Livingstons and non-Livingstons in upstate New York to claim him as an honorary son.

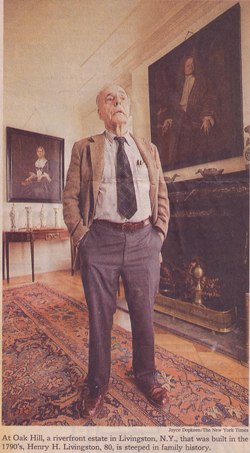

“I think this is great news, and we’re all very proud of him,” said Henry H. Livingston, a distant cousin who lives at Oak Hill, a 200-acre riverfront estate that was built in the 1790’s. “We’re not bragging, but this family is very interested in its history.”

Like so many blue-blooded families in the 20th century, though, the Livingstons have sometimes been bewildered by modernity, their fortunes watered down by income taxes, their sensibilities entrenched in a genteel time warp. So until the Congressman’s ascension to national prominence, few people talked about the Livingstons outside of the tour guides at the museums and historic sites dotting the area.To date, Mr. Livingston, the would-be Speaker, has not had much of a connection with the Hudson River Valley; he has only been here once, his sister said, and that was for a big family reunion at the Clermont State Historic Site in 1986. But should he return, he would find an area steeped in Livingstonia, one still shaped by the family’s influence. There is, of course, the town of Livingston in Columbia County. There is the village of Linlithgo, which, save for a dropped “w” at the end, is the same as the Congressman’s middle name. Linlithgo is the family’s ancestral home in Scotland.

Clermont, the town, is named after Clermont, the family mansion. The village of Blue Store is named after a tavern that was painted blue, and owned by a W. T. Livingston. There is also Linlithgo Mills (a village), Livingston Manor (a town in Sullivan County) and assorted local institutions, such as Livingston Memorial Church (which is in Linlithgo, naturally).

Then there is the name Robert Livingston. According to the family’s hefty genealogical register, which is decorated with the family’s coat of arms, there have been 63 Robert Livingstons. This includes five Robert Linlithgow Livingstons, of whom the Congressman would technically be the 4th, and his 32-year-old son, the 5th.

One Livingston family, unable to muster anything original, simply named one of their sons Livingston Livingston.

“There is no more of an old-money, blue-blood family in the United States than the Livingstons,” said Robert Engel, the curator of collections for the Clermont State Historic Site, a former Livingston homestead. “These people know their legacy, and what is amazing is how much they continue to protect that legacy.”

The family’s fortunes began in 1686, when Robert Livingston, a 32-year-old merchant from Scotland, bought 160,000 acres and called it Livingston Manor. By the early 1800’s, the family had built about 40 mansions on the Hudson’s east bank and had accumulated, through business deals and marriages to families like the Van Rensselaers and the Beekmans, one million acres, including most of the Catskills.

The Livingston men entered public life. The most famous was Robert R. Livingston, great-grandson of the First Lord, who was known as “The Chancellor” because he was the first Chancellor of the State of New York. He also helped draft the Declaration of Independence, negotiate the Louisiana Purchase and provide financial muscle for Robert Fulton’s steamboat, the Clermont.

Edward Livingston, brother of “The Chancellor,” was no slouch, either. He was the Mayor of New York City and the United States Attorney from the New York district – simultaneously. Then, after he learned that some aides had embezzled municipal funds, he resigned and moved to New Orleans, where he became a United States Senator and Andrew Jackson’s Secretary of State.

No other person in the family with the last name Livingston has made national news since the early 1800’s Mr. Engel said. But there have been many notable people with Livingston blood – so many, in fact, that the apropos question may well be who is not a Livingston?

Eleanor Roosevelt and Hamilton Fish were Livingstons. George Bush and his scions are Livingstons. So too, is former Gov. Thomas H. Kean of New Jersey, whose own home is in the township of – what else? – Livingston, N.J.

“The Livingstons were like the Kennedys: they were in politics, there were a million of them, and you can’t help but liken them to a dynasty,” said Lucy Kuriger, the site director of Montgomery Place, a historic estate in Annandale-on-Hudson that was last owned by Dennis Dolefield, a first cousin of the Louisiana Congressman.

But unlike, say, the Kennedys or the Bushes, the Livingstons have never been associated with one political party or ideology. Instead, they were more known for their baronial life style in an area that does not look much different now than it did generations ago, with its rolling hills, apple farms and sweeping river views.

Shuttling between their estates on the river and their commodious apartments in Manhattan, the Livingstons floated through a world defined by Old World grace and comportment and lubricated by cook servants and gardeners. And they usually did not venture outside their peer group. In the town of Tivoli, for instance, there used to be two churches: one for the Livingstons, one for hoi polloi.

“It was an absolutely differen world then, and they were like the landlord and we were like the tenant,” said Peter Fingar, 69, of Germantown, whose ancestors moved from Germany in 1710 and worked on the Livingstons’ land. “We didn’t break bread with them, any more than the English did with the queen.”

These days, the Livingston aura continues at Oak Hill, the home of Henry H. Livingston, a retired financial analyst, and at Rokeby Preserve, a 500-acre estate owned by Winthrop Aldrich, a deputy commissioner of historic preservation for New York State.

But the family’s influence on residents like Mr. Fingar has become muted, given that the family’s reach has become so ingrained into everyday life: Townsfolk drive down streets that were once the Livingstons’ private roads, they eat in restaurants where Livingstons once dined, they pass historic markers bearing the Livingston name.

Even so, the news of Mr. Livingston’s rise to Speaker of the House has engendered calls for a commemorative plaque. Donald R. Kline, Livingston’s Town Supervisor, has suggested putting up a marker in town noting the connection between the Livingstons of the past and the Livingstons of the present.

Not only do the plaques abound, so, too, do the stories.

One of the more popular, for instance, involves Philip Henry Livingston, who was a grandson of Philip Livingston, a signer of the Declaration of Independence.

A few years ago, Laura W. Murphy, a black woman and director of the national legislative office of the American Civil Liberties Union, discovered that she was a descendant of Philip Henry Livingston.

In 1812, Mr. Livingston had a daughter with a slave, Barbara Williams, but never acknowledged his liaison. Ms. Murphy mentioned this bond in a letter to the Congressman a couple of years ago. He has responded with class and good cheer, Ms. Murphy said, occasionally signing his letters as “Cousin Bob” and introducing Ms. Murphy as his cousin.

“We’re having a ball with it,” said Ms. Murphy, who lives in Washington. “He seems to embrace history.”

Indeed, Mr. Livingston is aware – if perhaps a bit wary – of his family’s history, having inherited boxes of family mementos and an oil portrait of their grandfather, said his sister, Carolyn Teaford, in a telephone interview from her home in New Orleans.

Their grandfather (Robert L. Livingston) was a banker in New York City who died of pneumonia in 1925.

His widow, who also came from a wealthy family, then took her five children to France.

Their father (also Robert L. Livingston) returned to the United States during World War II, attending Colorado College in Colorado Springs, Mrs. Teaford said. He met their mother there, and the future Congressman was born in 1943. After the war, they spent a few years in Tuxedo Park, N.Y., before the father got a job in New Orleans as a salesman for National Distillers.

It was a bad omen; he was an alcoholic, Mrs. Teaford said. In 1950, their parents divorced, and their father eventually fled to Spain to avoid paying alimony. But their mother persevered, found steady work and raised the two children.

As a result, they had little contact with the Livingston side of the family. But when they did meet, the Livingstons talked incessantly about the past.

“They loved to talk their family history; they were big on things like, `Now your great-great-grandfather did such and such,’ ” Mrs. Teaford recalled. “Certainly we’re proud of that, and it’s wonderful to have a heritage. But my brother and I believe it’s who you are, and what you do, and not who your ancestors are, that make you a person.”

Postscript: Henry H. Livingston died in November, 2008. His son Henry now lives at Oak Hill.